On the last blog How Your Spine Moves, we discussed the three directions of spinal movement, and the importance of regular movement. It is great to be aware of these three movements, and know how to incorporate them into your life and daily practices.

Recall that the planes of movement are flexion & extension, side bending (right and left), and rotation (right and left).

Although it is helpful to understand these movements individually, note that these movements do not happen in isolation, but rather our movement is typically moving in some combination of flexion/extension, side bending, and rotation. Our bodies move in patterns, rather than in a series of isolated movements. This speaks to the importance of practicing moving in a variety of directions, feeling the different shapes your spine can make.

Connecting the Planes into 3D Movement

From the hands and knees position, making circles with the spine is a great way to dynamically move through all three planes. This movement is more advanced than single plane movements, and it may take some time and practice to find ease with this pattern. With a keen awareness of an imaginary light from your tailbone, draw circles with that light on the wall behind you. Be sure to switch directions every so often! Just remember it doesn’t have to be perfect. Now that you can make circles, what other shapes can you make?

Another option for three dimensional movement would be making circles with your thigh, as demonstrated in this video. Engaging in these movements is an opportunity for you to feel and sense yourself without judgment, rather than trying to “achieve” something.

The bias towards one-dimensional movement

Just as our life can be biased towards movement involving forward flexion, our movement and exercise routines can also be biased in this way. If all of our movement practice involves moving primarily in one plane (e.g. the sagittal plane), we can sell ourselves short. While strength training machines at the gym can be very helpful for developing strength and muscle mass, they are typically constricted into one of the above described planes and thereby restrict our spine’s ability to move three dimensionally.

To be clear, we believe that strength training machines are brilliant at isolating muscles and enhancing overall conditioning. But the downside is that our nervous system, the little woman or the little guy in the control room of our brain gets more and more biased to think in terms of isolated movements rather than whole body patterns.

Think of throwing a ball and only moving your arm, rather than your whole body. Contrast that with turning first, flinging the arm back in the direction we are turning and then reversing the whole movement so that the arm is like a whip sending the ball so much further without strain on any one particular joint. Knowing how to integrate the movements of your body into three-dimensional patterns will improve the efficiency of your movement and thereby decrease the likelihood of strain and injury.

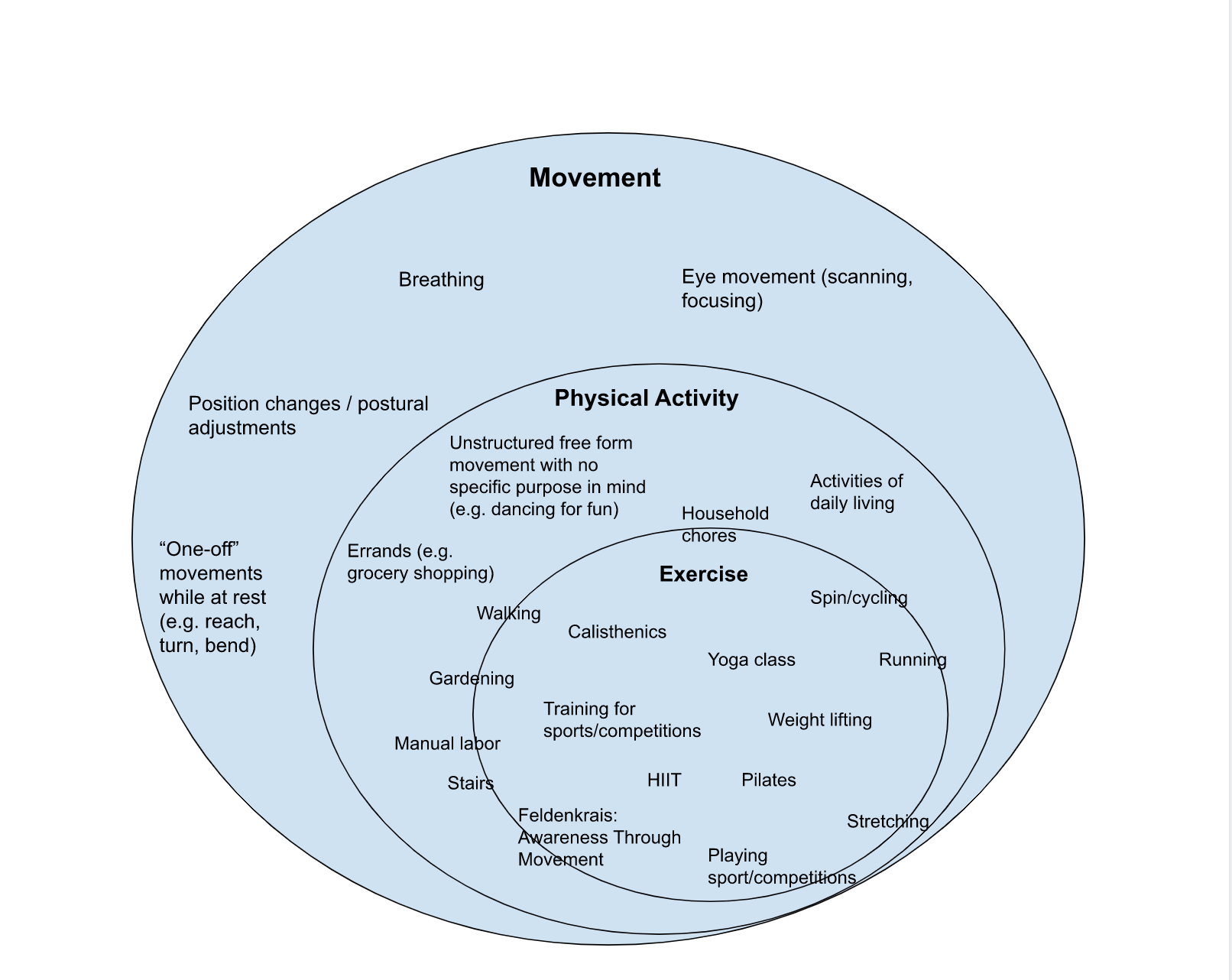

At the Wellness Station, we will teach you how your spine moves, and help you to expand your movement repertoire. We will encourage you to get involved in a regular movement practice that will include three-dimensional movements of your spine, such as Feldenkrais or yoga classes. Supporting the health and movement capacity of your spine will help you find a greater sense of ease and comfort in your body, while preparing you for successful participation in the unpredictable demands of life.

Written by Jacob Tyson, DPT - Physical Therapist, Yoga Instructor and The Wellness Station Team

Images: