Osteoarthritis (OA), which is also known as degenerative joint disease, involves a wearing down of the flexible cartilage tissue at the ends of the bones that form joints. It is the most common form of arthritis, and it is estimated that over 32.5 million US adults are affected by it!(1) Prevention strategies of arthritis before it occurs is the most effective way to make sure it will not become an issue in your life. These strategies may include improving movement patterns, staying active, keeping your muscles strong and joints flexible, having good nutrition while avoiding processed and pro-inflammatory foods, staying hydrated, maintaining a healthy weight, and ensuring adequate recovery from exercise with enough sleep and gentle movement.

Once a joint has become arthritic, what are some strategies to keep in mind to optimize functioning, improve joint health, and mitigate the impact that this condition could have on quality of life?

There is plenty of misinformation out there regarding arthritic joints. Even the terms used to describe OA colloquially can impact the public’s perception in a negative way. Degenerative joint disease. Wear and tear arthritis. Bone on bone! These types of descriptions bring scary images to mind, and imply that movement and exercise is actually unhealthy for joints and can contribute to joints wearing out. Certain doctors may tell their patients with OA that they should not do certain things any more- bend, lift, squat, kneel, run.

Too often, adults with arthritic joints begin to fear movement, or the pain that they may associate with movement, and will begin to exhibit compensations in the way they move. They may begin to become more sedentary, limit participation in various activities, and develop a resentful relationship with the involved body part. These changes contribute to a snowball effect, in which case the changes in mindset and behavior lead to further decline in joint function and tissue weakness, which continues the arthritic process, thereby leading to further pain, fear, and avoidance of movement and activity.

On the other hand, some people may overdo vigorous activity, which can increase inflammation and contribute to additional strain on compromised joints. It can be difficult to find the balance between too much and not enough. Lower impact, moderate activity performed on a consistent basis tends to be the sweet spot in which those with arthritis can keep their joints mobile and strong without contributing to flare ups and potential joint injury.

Movement is absolutely essential for all of us, and especially for those with OA. If the question is move or don’t move an arthritic joint, the answer is to move intelligently and often.

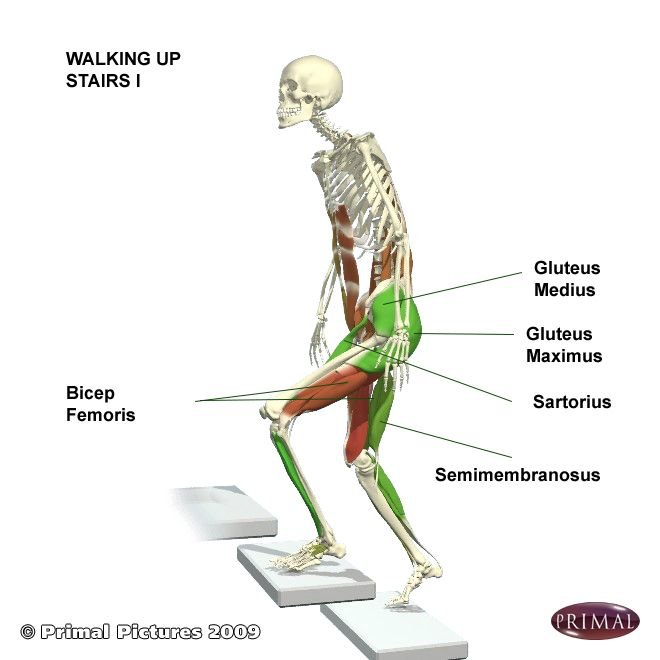

As arthritic joints tend to become hypersensitized to loading, we must load the joints efficiently without strain, and allow the muscles and other tissues around the joint to get stronger. Stronger, smarter muscles will provide shock absorption and support for the joints, which helps attenuate the forces from daily life, movement, and exercise (like having your own built-in knee brace!) Movement has been shown to limit pain and improve joint motion, as well as prevent the risk of a future injury or fall. (2)

Joints that become arthritic tend to be synovial joints, meaning the joints rely on synovial fluid (the lubricating WD-40 of our joints) to move smoothly. In order for the synovial fluid to stay healthy, slippery, and plentiful, we must move the joint! Movement of joints helps to improve synovial quality and distributes the fluid around the joint so we can move without friction. Additionally, movement helps to distribute blood flow (which contains nutrients and oxygen) around the joint tissues, and can help decrease excessive muscular tension which may be associated with a pain pattern. Exercise has even been shown to activate genes that can help to rebuild cartilage!2 Cartilage has a limited potential to rebuild, but it is possible, and the cartilage that we do have can be strengthened just like other tissues.

If you have OA, it can be very difficult to get your joint moving and begin the process of regaining strength and mobility. When joints have been painful for a long time, central sensitization may have occurred, which involves central nervous system changes in our perception and response to pain. The pain perceiving pathways may now be embedded deep into our brain circuits, including the prefrontal limbic regions, which is associated with our emotional responses. (3) Combined with structural, tissue-level changes, it is no surprise that many with OA fear movement and require guidance from a physical therapist or other health practitioner to get moving again. Fortunately, physical activity has been shown to have a positive effect on central sensitization, as it can help modulate the pain response by decreasing excitability in the motor cortex as well as stimulating the release of endogenous opioids (endorphins and other substances that are our brain’s natural pain relievers). (3)

At the Wellness Station, we will be able to guide you intelligently and compassionately towards building strength, improving function, and opening up your life to greater possibilities.

Here is one of my favorite, low-impact exercises for building strength and control in the lower body and core. This can be especially helpful for individuals with knee and/or hip arthritis, in which cases standing exercises like squatting may be inefficient and painful. Many people have done the “bridging” exercise. The Feldenkrais-inspired bridge is known as “spine like a chain”. It involves pressing through the feet to begin to lift one vertebrae at a time from the ground, and lowering down in reverse. This can help to strengthen the glutes and thigh muscles, mobilize the spine, and improve awareness of how we utilize the forces from the ground to move our bodies. Check out this video from Paul McAndrew to get a visual and verbal demonstration of the movement: Spine Like a Chain

Written by Jacob Tyson, DPT - Physical Therapist, Yoga Instructor and The Wellness Station Team