Have you ever been to a practitioner who assured you that the cause of your pain was one of the following, or some combination of these very technical sounding terms? “Your ____ (spine, hips, etc) is out of alignment.” “Your pelvis is twisted.” “Your SI joint is jammed.” “Your pain is because of your leg length discrepancy.” The list goes on and on.

These types of claims are not helpful, and can be downright destructive due to the nocebo effect.

First of all, joints don’t go “out”. If your joint was dislocated, it would be a medical emergency that you would be well aware of, and warrant a trip to the ER. Additionally, structural explanations for pain (aside from acute pain due to tissue injury) are generally unsupported by evidence. These claims (e.g. joints being “out”) have extremely low interrater reliability, meaning two different clinicians would almost never agree on them.(1)

By teaching people that these minor asymmetries are “serious”, clinicians are over-medicalizing normal human conditions. We all have asymmetries, and we do not have good evidence that asymmetries will lead to pain and dysfunction. By believing that your pain is structural, it is taking you out of the healing equation, and will consciously or subconsciously rely on external sources for healing, including surgeries, injections, and frequent chiropractic adjustments.

Fortunately, the human body is not like a car. Because issues as complex as pain are not due typically due to structure alone, they typically do not require a structural solution. Unlike a car, the human organism has a nervous system, an immune system, and higher consciousness that allows us to think, feel, move, make decisions, and change our beliefs and behaviors. It may be convenient for some clinicians to blame structural issues as a scapegoat, as it can be easier and quicker to explain than the other contributing factors, and can also be an effective business model. Also, many patients may also be looking for some structural issue to blame, as it can be extremely frustrating and distressing to be in pain for a long time and not understand why. However, it is crucial for clinicians to educate patients on the real causes of pain, and move away from teaching people the body is a machine that breaks down, inevitably leading to pain. We need to lean in to educating people on the messier science, including physiology, neuroscience, psychology, as well as social and lifestyle factors.

The truth is, pain is multifactorial. Sometimes it is very simple, sometimes it is extremely complex. Simple cases tend to be acute- you stub your toe, the nociceptors (pain receptors) fire, your brain registers the sensation as pain, and you say “Ow!”. However, chronic pain is a different beast. After pain persists and the initial injury is gone, brain changes tend to be what keeps the pain cycle alive. Our nervous system can get a bit confused, and the helpful pain perceiving pathways can start to run awry. We begin to get overly sensitive to stimuli that normally wouldn’t cause pain (known as allodynia), and perceive that pain is more intense than we normally would (hyperalgesia). It is very hard to turn that sensitivity back down, and it requires neuroplasticity (brain change).

So how do we change our brain to affect our pain? We have to address pain biopsychosocially, meaning we address the biology, the psychology, as well as social factors.

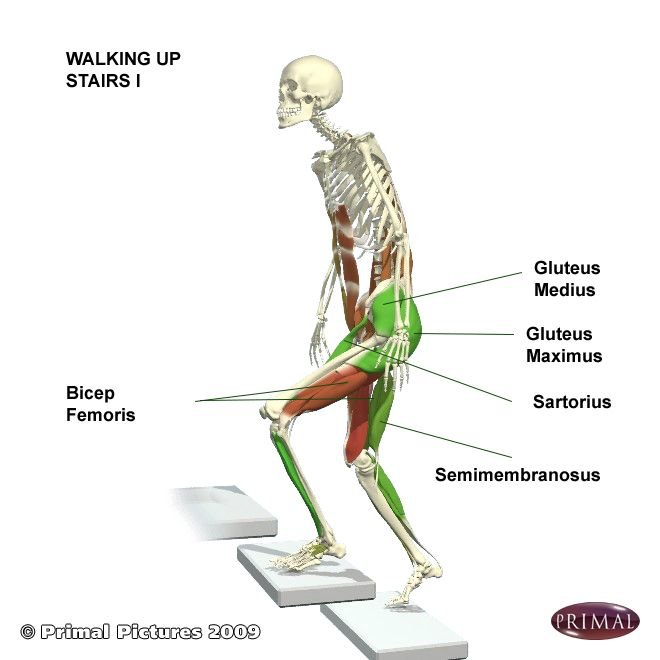

Biologically (or physiologically), we rehabilitate the physical body through movement and exercise, improving efficiency of movement, decreasing unnecessary tension, and improving fitness. This might mean gradually desensitizing our body to painful movements or activities. We also want to make sure we are sleeping well, eating healthful foods, staying hydrated, and being very mindful regarding consumption of certain substances.

To address psychology, we must challenge our beliefs, improve our mental health, find appropriate coping mechanisms for stress, and change our relationship to our pain to become less reactive and more responsive.

To address the social factors, we have to make sure we are surrounding ourselves with the right people, participating in activities that bring us joy, and seeking support rather than battling with pain alone.

Hopefully, this path to healing does not seem overwhelming. By addressing these biopsychosocial factors, we can take control of our lives and make decisions that better ourselves and improve our quality of life. We can take an active role in our own healing, and won’t be as reliant on expensive and harmful procedures. While the healing journey is not linear and will come with challenges, it is the direction to go for all of us, with and without chronic pain.

It is our job at the Wellness Station to take the role as educator, detective, and coach. We strive to teach you about the science of pain, figure out the greatest contributor factors, and provide guidance, encouragement and support as you begin or continue your healing journey.

References:

Written by Jacob Tyson, DPT - Physical Therapist, Yoga Instructor and The Wellness Station Team