We live in a three-dimensional world, and our body is meant to move in all three dimensions (See our past blog post, Moving in Three Dimensions). Our spine, which contains 24 moveable vertebrae, has the capability of moving in these three planes.

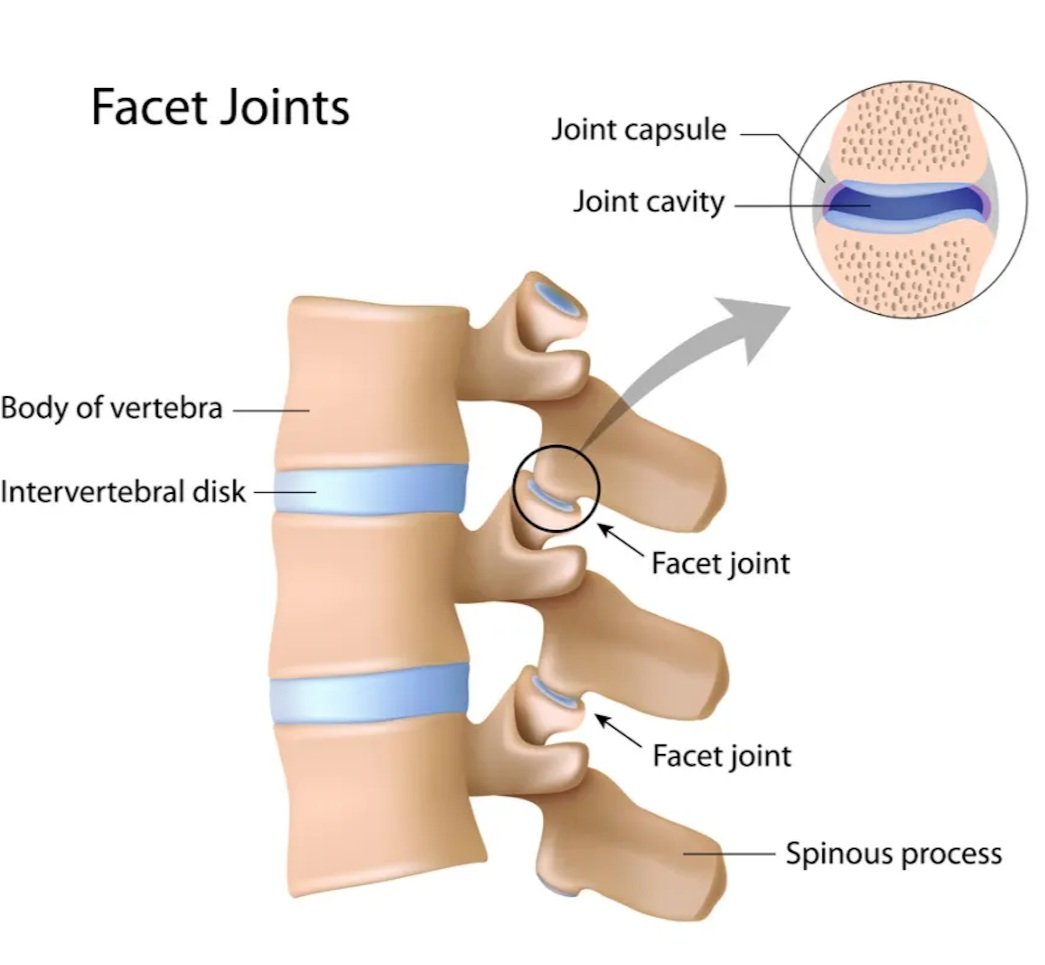

The facet joints of your spine are the joints at which point each vertebrae meets the one above and below on the side. These are synovial joints, they require regular movement in order to stay lubricated and nourished with nutrient-rich fluids.

By understanding how the spine moves, and regularly moving it in a variety of ways, we can keep our spines healthy, the tissues nourished and supple.

Life can be unpredictable, and we might find ourselves in random shapes in order to meet the needs of our environment. Reaching for that pan located awkwardly in the back of the cabinet? Your spine needs to change its shape. Turning towards your backseat to pick up the glove you dropped last week? Again, your spine needs to change its shape. Having trouble reaching overhead to get the glass from the highest shelf? Again, shape change is required.

If we can train our spine to change shapes with ease and comfort, daily tasks are easier and less likely to contribute to strain. The mobility of our spine is so interconnected with our quality of life, as the loss of mobility can make these daily tasks that much more difficult.

The process of engaging in mindful spinal movements can help ease tension, improve tissue health, enhance body awareness, and feel really good!

As we go through life, we might gradually incorporate less variety or spontaneity in what we do. This goes along with our spinal joints moving with less variability, and thereby becoming less supple and possibly stiff in certain directions and ranges of motion (use it or lose it phenomenon). Most of our lives are biased towards activities that bring us down and forward, so over time it can become more difficult to extend, rotate, and bend from side to side. Imagine how you feel after sitting, hunched over a computer for several hours. Or perhaps after a long car drive. Can you feel the relief that moving your spine the opposite direction (extension) can bring- such as by reaching to the sky and following your hands with your face and eyes?

Our tissues do not like to be stuck in the same position for extended times or do the same repetitive task without variations. Without incorporating variety into how we are moving, our spines will not move as comfortably as they once did. Take a look at our Movement Snacks blog for some ideas on how to move your spine in different directions, the perfect antidote to prolonged sitting.

Directions of Motion

The 24 moveable joints of the spine permit movement in three planes, as described below. The joints that move are located through the neck (cervical spine), upper and mid back (thoracic spine), and lower back (lumbar spine), and below are the sacrum and coccyx (tailbone) which contain fused (non-moving) joints. The moveable regions of the spine have different capabilities in how much they can move in each direction, but are all capable of flexion, extension, side bending, and rotation, as described below.

Flexion and extension

Flexion and extension are movements that happen in the sagittal plane, which includes forward and backward movements. Flexion (AKA rounding) involves a forward bending of the spine, which often happens when we look down, bend down, and reach down to tie our shoes.

Extension (AKA arching) is involved in looking up and reaching up. Typically, we can flex much further than we can extend, and our cervical and lumbar spine tend to have more sagittal plane range of motion than our thoracic spine. The mid back, the rib cage/thoracic area, is designed more to flex, thus the tendency for many of us as we age to present a more rounded/slumped posture.

The cat cow, also known as the hill and valley, are a great way to feel your spine moving through a range of flexion and extension. Try to notice how you are initiating flexion and extension, and where in your body you can feel the movement happening (e.g. regions of the spine). Imagine there is a light shining from the end of your tailbone (coccyx). When doing a slow, easy cat cow, can you notice that light would be moving up and down throughout the movement?

Side Bending (Right and Left)

Side bending movements happen in the frontal plane. These movements involve one side of our body (e.g. right vs left) getting longer as the other gets shorter. Side bending may be involved in reaching, stairs, and lifting an object from one side of our body. Our cervical spine tends to have the most capability of side bending, followed by our lumbar, then our thoracic.

Lateral cat cow, also known as tail wagging, is a great way to feel your spine’s ability to bend side to side. Considering the light from your tailbone, can you perceive that the light would be moving from side to side, like wagging your imaginary tail right and left?

Rotation (Right and Left)

Movement in the transverse plane involves rotational movements, rotating to the right and left. These movements can be involved in turning around, looking from side to side, reaching behind or to the side, repositioning in bed, and more. Our cervical spine tends to have the most capability of rotation, followed by our thoracic, then our lumbar.

A thread-the-needle type of movement on hands and knees is a great way to feel rotation of your spine, and to sense how rotation is connected to the reaching of our arms. Notice an imaginary light shining from your chest bone. Where does this light move?

Now that you know the three directions of spinal movement, try to pay attention to your movements throughout the day or during your exercise routine. What plane do you move in most often? What plane do you move the least in? What parts of your spine feel more freedom of movement within each plane? The process of self-study will support mindfulness and self-awareness, and begin to harness your ability to listen to your body and respond accordingly. This ability will guide you towards making substantial improvements in function, patterns of pain, and will help you stay comfortable in your body as you move through life.

Written by Jacob Tyson, DPT - Physical Therapist, Yoga Instructor and The Wellness Station Team

Images: